Global Day of CodeRetreat: Pittsburgh

As I mentioned on Sunday in introducing CSEdWeek, Saturday was the ambitious Global Day of CodeRetreat, whose local Pittsburgh edition I participated in, with around 50 of us total. The global event was held simultaneously in 90 cities and had around 2000 attendees. I had a great time, although I was totally exhausted by the time it was over (it lasted from before 9 AM to after 6 PM; what a way to spend a Saturday!).

What is CodeRetreat and what can you get out of it as a software developer?

The CodeRetreat concept

CodeRetreat is the brainchild of Corey Haines. The motto is “Programmers honing their craft together.” The basic idea is the programmers gather for an all-day event in which they pair up with different partners for six sessions to work again and again on the same problem, starting from scratch each time. You can read about more formal details, but I didn’t before I went to the event, and in this post I will walk through my experience as a first-time participant.

If CodeRetreat already sounds weird, it’s because it is. I had heard about it earlier from a couple of people I’d met at the Pittsburgh Geek Out Day sessions who had gone to such events in the past. To be completely honest, the first time I heard about it, it sounded weird. And the second time, after hearing about the session held in Pittsburgh in May when I was out of town, it sounded weird too. But I’m the kind of person who is willing to try weird things if I don’t believe they can be actively harmful and have a chance of being very beneficial.

I’m going to state up front that if you are a programmer and haven’t been to a CodeRetreat, and one is happening in your area, you should try it out.

Morning introduction

I arrived before 8:30 AM, in time for taking a seat at a table and doing some socializing over coffee and donuts/bagels. Socializing is one of the big reasons to go to an event like this; I had never been in a room of fifty local developers from all kinds of domain and programming language backgrounds.

We were told that our task was to implement Conway’s game of life. Actually, we all already knew that, because we had been informed before the event. To keep myself fresh for the event, I deliberately did no thinking about the problem, working on an algorithm, or coding it. I do not know how many other people took this attitude, and am curious how it affects the nature of participation (I will discuss some speculations later in this post).

First session

I don’t remember what specific instructions we were given for our first session, other than to pair up. I may have been too distracted by the socializing at the time. It would have been useful to have received handouts to guide us. I do know that at some point in the morning, before the first or second session, we were directed to look at the whiteboard that had the “four rules of simple design” written on it:

Four rules of simple design

- Passes all tests

- Clear, expressive, consistent

- Duplicates no behavior, config

- Minimal methods, classes, modules

My first pairing experience

I’d heard about pair programming for a decade, in the context of Extreme Programming (XP), but had never practiced it. To be honest, as late as a year ago I found the concept very strange and distasteful. Interestingly, by this year, as a result of participating in a lot of local programmer group meetings, I became more sociable generally and more amenable to real-time sharing of ideas. Part of the reason I decided to go to CodeRetreat was to experience pairing.

For the first session, I paired with Adam, since I knew him (in fact, I had gotten him to register at the last minute for the event) and we could work together in Java.

We gathered around his laptop, and spent quite a bit of time (of the allotted 45 minutes per session) sketching out a design for implementing Conway’s game of life. First we had to decide what variant of the game to implement: fixed grid with boundary or infinite? We decided on infinite. Then we had to figure out an appropriate algorithm and data representation. We came up with that. We ended up writing scaffolding for a complete application, for initializing the grid, displaying it, computing the next step, etc. Unfortunately, time expired when we were just about to implement the rules for the game.

Then we were told to delete all our code. That was kind of shocking. We weren’t allowed to just archive it somewhere. We had to delete it right there and then:

Observations

I was disappointed that we didn’t have something to show after 45 minutes. I was also shocked about having to delete our work. I felt that the infrastructure we had set up was valuable. I was confused by how what we were doing was contrary with how I would operate in real life on a real programming project. 45 minutes was not enough time to do the kinds of things I really wanted to do.

Meanwhile, at some point I realized that we had violated the “rules of simple design”. We had a proliferation of interfaces and in fact we kept changing them in order to be able to compile while nearing something that could actually run.

Second session

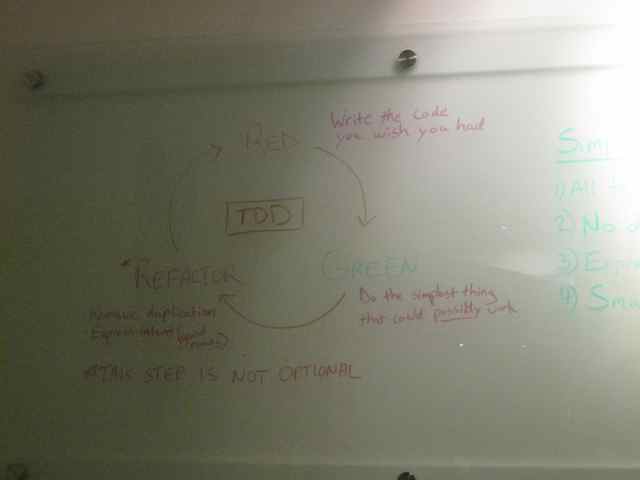

I think that for the second session we were instructed to use test-driven development:

I looked for another Java programmer, and paired with Heath, whom I had met earlier in various events but never worked with. We had some ideas based on what we each had done in the first session and got going. This time, we used my laptop, and the first thing I did was start writing tests with JUnit.

We made good progress, but I felt hampered by Java’s verbose syntax, and also I confess to copying and pasting test setup code just because time was short. I ended up feeling conflicted because the time constraints of this event were generating powerful perverse incentives. I think a lot of us kind of liked the idea of getting something working and done, and cut corners throughout the day. This is something that should be addressed by the CodeRetreat organizers and facilitators. After each session, many of us ended up saying, “We almost finished!” or something like that. I tried to resist having that mentality, but it was difficult given the time limit.

Third session

The final morning session had me pairing with a Python programmer, Joe.

We were supposed to do “ping pong pairing”, which I hadn’t heard of before. The idea was to take turns being the one writing tests and being the one writing code to pass the tests.

Joe and I wasted some time getting set up with Dropbox so that we could use both our laptops in order to get concurrency benefits.

I started out writing tests using unittest and Joe wrote the game implementation. It turned out we never actually ping-ponged, so we violated the intent of the session. We both got into the idea of being able to get something done. In particular, we agreed on a purely functional algorithm, which we knew would be expressible very compactly in Python.

We ran into concurrency problems because we were perpetually editing source files such that I kept seeing an out of date version of his code and vice versa. “Concurrent” development using something like Git is one thing, but having one’s view of a project change underneath one’s feet is another. I don’t think the Dropbox idea worked so well, but a number of us that day independently came up with it and spread it around and used it. I now think that’s not only cheating, but it even further distances the situation from that of real life software development!

Also, in the end, Joe had written a lot more code than we had tested, and I had written a lot more tests that were not yet passing. So I think the experiment didn’t work out well. We were not keeping to the TDD cycle we were supposed to keep to, in which a test is written, code is written to pass it, then another test written making the code fail, etc.

Lunch

For various reasons, we kept falling behind schedule in the morning, such that it was later than planned when we finally took a lunch break. We each got a nice box lunch, and I took a short nap before resuming more socialization and discussion, which was finally interrupted when we had to begin the afternoon sessions.

Fourth session

The fourth session was supposed to be “mute ping pong pairing with loophole”, in which we were not supposed to communicate except through code, and the one writing code to pass tests was supposed to be fiendish and write code that would pass the existing tests but would clearly not be the correct long-term code for the problem at hand.

I paired with Chris, using Java, and we did the Dropbox thing. Unfortunately, we spent a large amount of time getting set up. We both had problems connecting to the WiFi for a while. Furthermore, we finally realized that two machines both running IntelliJ IDEA on the same project was a bad idea, because of clobbering of project state. I switched to Emacs, but then we had to rig up a script for me to be able to compile and run stuff he was generating in IntelliJ IDEA. There was just too much setup time wasted.

Chris took up the test-writing duties and I proceeded to write code. This was my first time during the day to write code to pass someone else’s tests, so the experience was quite interesting. Thanks to static typing, the tests Chris wrote forced me to write various classes and methods. I did play the trick of writing degenerate code that passed one of his tests and forced him to write more tests.

We ran out of time before we got to ping pong the roles. Oops. I did learn something from this “no talking about design up front” session though: tests can go a long way to drive and constrain the kinds of designs possible to solve a problem. And I was clearly not writing anything extra when focusing purely on passing the existing tests.

Fifth session

The fifth session was supposed to be “open” to however we wanted to go about implementing the game.

I was paired with Demeng, who uses C#, which I have never used. It was not clear to me what we should do. Somehow, we ended up deciding to have me work on a Haskell implementation of a general design we discussed, so that he could watch and ask me questions and learn some Haskell in the process as I explained to him how to express something we wanted. Given that he was familiar with Python, I felt this was a feasible goal, and it was going quite well, actually. I would write a line of code and explain it to him, or he would tell me something to express, and I would write the code.

Unfortunately, I was still not set up for production Haskell development, e.g., with a testing framework, so we had ad hoc tests.

Sixth session

The sixth session had each pair rotate to the right to work on someone’s machine and code from the fifth session.

This was quite traumatic for some of us.

Demeng and I got moved to a laptop with C# going. He took charge, but I felt somewhat helpless because I had to keep asking about various C# constructs, and also, the original programmers didn’t use a testing framework that made it easy to start looking at the existing tests and write more. Even worse, it was getting late and Demeng had to leave, so I was left alone trying to figure out what was going on.

The pair who ended up with my Haskell code was in even worse shape. They didn’t know any Haskell, and were fairly confused and kept on asking me for help. They didn’t manage to write any code that compiled. I felt bad about having used Haskell in the fifth session without knowing that it was going to become a new pair’s legacy code!

What I got out of CodeRetreat

I’m not sure I got what was “intended” out of CodeRetreat, if the intent was for us to rigorously follow the guidelines and rules we were given. There were too many perverse incentives and little enforcement. Also, the frictions of different languages, IDEs, and operating systems were sometimes significant.

What I mostly got out of CodeRetreat was value at a meta-level. It was a time to socialize, to meet new people and even work with them. It was a time for many participants who had yet heard about TDD and various design principles to thinking about them and give them a try. It was a time to learn about other languages and development environments, even if only at a shallow level. It was a time for exploring different algorithms and data structures for the same problem.

The most concrete thing I learned was that pairing can be very stimulating and useful. CodeRetreat has made me think that I can definitely imagine pairing as a regular work practice.

Education and CS Ed Week

Although I think less chaos and more guidance would improve CodeRetreat, something about the whole process of getting people together and making them share is in itself a great example of learning and teaching. I’d call CodeRetreat an example of “education”, even though it is far removed from the conventional lecture hall. Nobody leaves CodeRetreat with a huge set of additional facts in the brain, but I’m sure many of us leave having experienced a taste of many ideas, shared recommendations to appropriate books and web sites to examine and study, and notions of how to change our actual practices in the real world.

What does any of this have to do with CS Ed Week? I think there is tension in the educational system between those who believe it should teach fundamental (usually meaning mathematical and abstract) foundations of computing, and those who believe that students should also be prepared for the messiness and realities of the “real world”. Meanwhile, a lot of the press concerning CS Ed Week focuses on very pragmatic arguments that the US badly needs more appropriately trained employees for computing jobs.

I don’t see how it is possible to really attract more young people into computing without at least helping them understand what a career in computing might entail. That requires some kind of exposure to what we actually do. It’s not enough to just teach a middle school student some kid-friendly programming language, or to teach a vocational student Java, or to teach an undergrad the details of Fibonacci heaps. The big picture is missing.

Events similar to CodeRetreat could play a role in getting a lot of people exposure to the big picture. Furthermore, even many of us who already work in computing do not see the big picture, because it is so easy to get out of date once out of school and working in some narrow niche. So “continuing education” is just as important as education at K-12 or in undergrad or grad school.

Concerns about CodeRetreat

It’s not clear to me that Conway’s game of life is such a good topic. It’s not very much like typical programming tasks. In fact, my mind wandered toward thinking about clever ideas for preprocessing, compilation, parallelization, and memoization that I’m not sure I would want to work on with someone for 45 minutes. I brought up this concern at lunch but was told that the task always remains the same because it serves its purpose, it works, and consistency is important.

There needs to be a way to help us resist perverse incentives to finish an app.

We should be better prepared to cope with different languages and development environments.

Will I attend the next CodeRetreat in Pittsburgh?

I have to confess that I do not know whether I will decide it worthwhile to go to another one. It’s too early to think about that, although Jim Hurne has already set February 25 as the date for the next one! I still have to fully digest what I experienced, make use of it, and then think about how I would maximally benefit from and contribute to another CodeRetreat.

Thank you!

Thank you, Vivisimo and M*Modal, for being sponsors and hosts for the event.

Thanks you, Jim Hurne, for putting so much work into not only the Pittsburgh event, but more broadly, the global one.

Thanks you, Andrew Cox and Joseph Kramer, for acting as facilitators all day (Andrew has written up a detail account of his experience on Saturday as a facilitator.

Thank you, Adam, Heath, Joe, Chris, Demeng, for pairing with me.

And thanks to everyone else who was at CodeRetreat.

Thanks for the write-up. I hadn't heard of these things before. It's an interesting idea, but I think I would be similarly frustrated by 45-minute sessions.