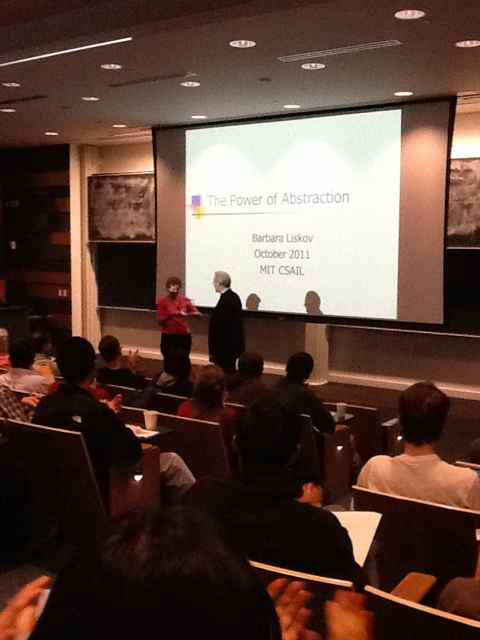

Seeing the inventor of the abstract data type

(Important update added to the end of this post.)

Today at CMU, I finally had the opportunity to see a living legend, Barbara Liskov, computer science professor at MIT and winner of the Turing Award in 2008. She won it largely for her invention of the abstract data type, a concept that is so foundational in modern software development that a programmer ignorant of history is likely to react, “What, she got a Turing Award for something so obvious?”

But that’s the beauty of computer science: it is such a young field that many of the ideas we take for granted now were not so obvious decades ago, and had to be discovered and codified and explained.

I had to leave Liskov’s talk right after she was done (it had already run over time), so I missed the question-and-answer session, unfortunately. I had been considering asking some questions, but since I lost that opportunity, I will pose them here instead.

The invention of the abstract data type

Basically, Liskov formalized the notion of the abstract data type (ADT) while at MIT in the early 1970s, and with some graduate students implemented ADTs as a fundamental construct in an actual programming language, CLU.

Most of you probably haven’t heard of CLU, unless you went to MIT where it’s been used for ages in courses. I only know about CLU because a long time ago, I had an MIT friend who mentioned CLU when I was asking him what to learn to become a programmer. I never actually wrote or ran a program in CLU, although I did take a look at the language. Some features of CLU (recall that it was developed in the early 1970s):

- modules (called “clusters”)

- information hiding

- static typing, including what are now called generics

- iterators (what we now usually call generators)

- exception handling

- garbage collection

Think about it. Java, developed two decades after CLU, didn’t even have generics. And it does not have true iterators.

A tangent on technology adoption

If you are in industry, a lesson to take away is that there is probably computer science research in academia right now that is useful but you won’t be using for twenty or thirty years.

If you are in academia, you might want to consider helping get good technology out the door before industry wastes two or three decades flailing around using inferior or broken ideas. (In fact, Liskov in her talk today noted that she had considered commercializing CLU.)

Influence on other languages

Liskov chose in her initial work to focus on data abstraction, rather than unify that with object-orientation, which had begun being implemented in the 1960s by Simula, but later contributed to the understanding of subtyping in object-oriented languages.

C++ took templates and exceptions from CLU. (Java, of course, took them from C++.)

Python, Ruby and other newer languages include iterators. To clarify: C++ and Java have “iterators” of a much different variety, which are just ordinary objects that have been implemented in often a convoluted way to maintain state for iterating through another object. The “real” iterators operate in conjunction with a special language construct usually called yield.

Questions I have

The world is globalized and connected now much more than it was back in the 1970s. So sometimes I wonder, what if it had been more connected in the past?

The C world

C was developed between 1969 and 1973. Dennis Ritchie wrote a little article, “The Development of the C Language”, in which he acknowledged the debt to Fortran and Algol. However, its goal as a low-level language for implementing Unix meant that it cut various corners. I wonder if the history of computing would have been different had there been more attention paid, even in the constrained context of Unix implementation, to interesting academic work. I don’t know what Ritchie and Thompson and others knew, if anything, about the work on modularity, types, etc. Maybe they knew, but didn’t care because they were building something just for themselves and they were such good programmers they didn’t need any help writing great code. It would be interesting, as a matter of historical record, to know who knew what and thought what, when.

The functional programming world

Absent from Liskov’s talk was any mention of the functional programming world. ML came on the scene also in the 1970s. Later, Standard ML came along. I don’t know the details of the exact chronology, but Standard ML had polymorphism and exceptions right off the bat, and a module system added on top of that.

Conclusion

Liskov’s talk involved a lot of tracing of the history of ideas that led to her contributions.

I am very curious about what influenced what, in the entire space of the history of programming languages. Obviously, a lot of ideas were floating around in the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s, so it’s possible that many programming language features were invented independently from the same pool of rough ideas.

Sometimes I wonder whether continual reinvention could be minimized, by more sharing and awareness. Even today there is a proliferation of languages, many of which were or are invented by some individual who is not aware of the full history or rigorous achievements in the area of programming language semantics or design, and therefore perpetuate problems that for decades already we have known to avoid. I wonder if this situation is really inevitable.

Of course, the question might be moot, because it is always possible that human beings will simply make radically different choices, even when they are fully aware of all the ideas that are around at any given time.

What’s the next step? What will we using doing twenty years from now that is currently already brewing in a university or other research lab right now? From my point of view, the most interesting work being done right now is that focused on going beyond the currently most powerful statically typed languages (such as ML, Haskell, Scala) to dependently typed languages.

(Update)

I have been told that it is misleading to describe Liskov as “the inventor of the abstract data type”. I admit this was a terrible title for my talk report. The content of my report should make it clear that I was baffled by Liskov’s omission of entire lines of research from the 1970s that address data abstraction, whether through ML or John Reynolds’ work. See Bob Harper’s Disqus comment here for his own elaborations.

It's quite true that we've been on a path of retardation over the last decade or so, with old lessons being ignored, and old mistakes being repeated, over and over. In most respects Java was a giant step backwards from CLU, as Barbara pointed out. Shockingly, though, she seems to have bought into some of the object nonsense, including especially its solipsistic emphasis on itself. The most glaring weakness of object-oriented languages is the complete inability to work with two or more abstractions simultaneously. CLU is more able to do this than Java or its derivatives.

Regarding the history of data abstraction, there is more to the story than was outlined yesterday. In particular Robin Milner invented a perfectly modern (more so than CLU) data abstraction mechanism for ML in order to ensure that a tactic-based theorem prover would never deem something a theorem that is not in fact a theorem. Reynolds contemporaneously introduced the theory of polymorphism, which includes as a special case the theory of data abstraction, and proved real theorems about it. (A methodology is what you're left with when you don't have a theory; Reynolds had a theory of what he was doing, and it has withstood the test of time.)

CLU was moderately interesting in 1979, but it was already clear from the introduction of ML a year or so earlier that the future was with ML, not with CLU. I would say that CLU represented the last serious effort at an imperative programming model, but it was quickly left in the dust by languages that support more than just imperative programming. All the business about iterators, so beloved by those deluded by object nonsense, is completely otiose if you have higher-order functions (which even lgol-60 had! In 1960!) The business about specifying exceptions in the type only works (sort-of) for first-order languages; as soon as you have indirection, via higher-order functions or via objects, these declarations are utterly useless. (Anyone who has used the visitor pattern, or the Java RMI, or anything else higher-order knows perfectly well that the throws clauses are useless.) Moreover, in a language with an expressive exception mechanism, such as ML, one cannot, even in principle, name the exceptions that can be raised by a piece of code, so the whole idea is really naive and unworkable.

The goal of striving for simplicity in CLU is laughable in that the simplest thing to do would have been to be higher-order in the first place. But then you'd have Algol, and whole enterprise would be largely just an extension of Algol with an abstraction mechanism. Not a bad thing at all, but in itself only an increment on a decrement from what was already known.